In 1985, I was a far bigger fan of jazz guitarist Pat Metheny than just about any other musician. The album that infected me was 1982's Offramp, which sounded unlike anything else I'd ever heard. I became a hardcore consumer of any and all vinyl featuring either Metheny or his compositional partner in the Pat Metheny Group, pianist Lyle Mays. (My friends and I could and did spend hours debating the meaning of the 20-minute title track from As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls. Yes, we were not normal.)

Thus it was inevitable, thirty years ago, that I would buy the new album from the Pat Metheny Group as soon as it appeared, even if it was the soundtrack to a movie I had not seen. I had a vague understanding of the true-life espionage case behind The Falcon and the Snowman (based on the book by Robert Lindsey), which told the story of Christopher Boyce and Daulton Lee, two young men from southern California who were arrested in 1977 for selling intelligence secrets to the Soviet Union. (Boyce was a falconry enthusiast and Lee a cocaine dealer, which is where their sobriquets came from.) I always meant to see the film, but never did.

But that didn't affect my enjoyment of the soundtrack. In fact, it might have enhanced it, as I could listen and try to imagine what was happening on screen during each passage. It wasn't my favorite Metheny album by any means, but parts of it I liked quite a lot. I even grudgingly came to enjoy the collaboration with David Bowie that kicked off side 2 of the record, "This Is Not America"—though I disliked the way the credits on the single made it seem like the Pat Metheny Group was just Bowie's backing band.

Anyway, it was late in 1985, when I was 18, after I'd been living with the album for eight or nine months, that a close friend of mine, whom I call "Andy Kilmer" in The Accidental Terrorist, came to me with a request. This passage is from the book:

Andy’s angst became acute in October 1985, when he received his mission call to Brazil. Slated to enter the MTC in January for eight weeks of Portuguese immersion, he asked me a favor. “You know that opening track from the Falcon and the Snowman soundtrack?”

“Sure,” I said. Our musical heroes Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays had composed the score. The first track was a choral arrangement of Psalm 121. “What about it?”

A sly grin creased his face. “Do you think you could transcribe it? I want my family to sing it at my farewell.”

It was LDS tradition that the family of a departing missionary arranged the program for his last sacrament meeting at home—choosing the hymns, assigning the speakers, and supplying special musical numbers.

“I love it,” I said. I was sure his congregation would find the piece reverent and sublime, but they wouldn’t hear the subtext. “I’m on it.”

I set to work that night, crouched over the piano, running a cassette tape forward and back, picking out the four-part harmonies, scrawling notes on a sheet of staff paper. I proudly delivered copies of my transcription to Andy a few days later.

On a cold Sunday in January, Andy and a chorus of his more musical relatives stood up before the Kaysville 10th Ward and lifted their voices in song. While most listeners heard a haunting plea for God’s companionship, for Andy and me the music conjured visions of Timothy Hutton and Sean Penn selling out their country.

It was our big middle finger to the church. We knew what it was doing to us, but it didn’t know what we were doing back.

Of course, it was an empty gesture.

Obviously Andy and I felt a deep attraction to that soundtrack, if not for the idea of two young men secretly defying everything their community stands for. I had no clue that I would eventually come to find many more points of connection with the movie and the story behind it.

The first—and for many years only—new connection was geographical. In 1980, Christopher Boyce escaped from the federal penitentiary at Lompoc, California. (His escape was outside the scope of the movie, but is chronicled in Lindsey's follow-up book, The Flight of the Falcon.) For eighteen months, he hid in plain sight outside of Bonners Ferry, Idaho, often hanging out with the locals in town, some of whom knew exactly who he was and did not care. He financed his activities during this period by robbing banks. He hit thirteen before he was finally recaptured.

I served as a missionary in Bonners Ferry for five months in 1987. My companion and I lived in a farmhouse outside of town, and we frequently drove the twisty, unpaved mountain roads to knock at the doors of cabins like the one where Boyce hid out. Several people in Bonners Ferry regaled me with the story of how the infamous Falcon was apprehended right in their little town.

So, I had tried to escape from my mission and ended up in Bonners Ferry. Christopher Boyce escaped from prison and ended up there too.

At some point during the intervening years, I know I watched The Falcon and the Snowman, but I couldn't remember much about it. A few weeks ago, after the latest draft of my memoir was done, I figured I should watch it again. The movie starts with Christopher Boyce (played by Timothy Hutton) quitting his Catholic seminary. I could sympathize with that right off the bat. His father, a retired FBI agent, pulls strings to get him a job with a defense contractor, essentially keeping him in the family business despite the fact that Christopher didn't really believe in the cause. Having been coerced into following my father's example and reluctantly entering missionary serivce, I could sympathize with that too. His relationship with his father appears to have been similarly dysfunctional to mine.

Christopher ends up working in a top-secret communications vault where he has access to CIA transmissions. He and his colleagues in the vault seem to spend more time loafing than actually doing their jobs. At the very least, their discipline is hardly up to snuff. That was pretty much how I was as a missionary, and is what led me to question what I was doing and go AWOL from Canada at the end of 1986. Christopher in the movie, on the other hand, sees CIA messages that make him question the morality of what he's doing, and he, um, well ... he gets his friend Daulton the coke dealer to sell the intelligence to the Soviets at their embassy in Mexico City.

Anyway. Things get out of control, of course, and Christopher and Daulton are soon in way over their heads. Their extreme incompetence as spies lands them in prison for a very, very long time. The end.

As for me, my incompetence as a criminal landed me in jail, too, albeit briefly. Watching The Falcon and the Snowman is, for me, eerily like peering into a parallel universe that feels like a place I could have ended up if not for a couple of lucky tosses of the dice. * Daulton Lee was not paroled until 1998 (after which he became a personal assistant to Sean Penn, who had played him in the movie). Christopher Boyce was very lucky to get parole in 2002. If I had spent a comparable amount of time behind bars, I would only have been released within the past few years. My life would be completely different.

The Falcon and the Snowman is more than just a movie. It's a brutal reminder that, if our lives are comfortable and uneventful, it's only chance that makes it so. Even with the best intentions, one wrong decision can trigger a catastrophic seismic shift.

And while I can't exactly sympathize with a traitor and bank robber like Christopher Boyce, I can't exactly not sympathize either.

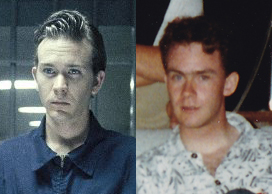

* Eerie too because the young me looked a whole lot like the young Timothy Hutton, making it all too easy to see myself in his shoes. Same gangly frame, same thin face, same eyes and nose. When I was a missionary, my girlfriend thought the resemblance was so strong that she used to sign her letters Debra Winger—in hindsight, maybe not the best portent.

For further reading:

The Falcon and the Snowman: A True Story of Friendship and Espionage by Robert Lindsey

The Flight of the Falcon: The True Story of the Escape and Manhunt for America's Most Wanted Spy by Robert Lindsey

American Sons: The Untold Story of the Falcon and the Snowman by Christopher Boyce, Cait Boyce & Vince Font