This essay is excerpted from The Accidental Terrorist: Confessions of a Reluctant Missionary, available everywhere November 10, 2015.

WARNING: This essay contains graphic descriptions of primitive surgery that some readers may find disturbing.

In January 1994, when I was 26 years old, I sat down in my bare, cold room to write my first novel.

In many ways, yes, the conditions were ideal. I had no commitments, nothing else to do, nowhere to be, and no worries for the moment about money. I’d been honing my craft for years with short fiction, and my third story for a major magazine had just appeared in print. I’d taken a stab already at the story I wanted to tell, in the form of a 30,000-word novella, and I’d thought long and hard about how best to expand that piece to novel length. I knew my invented world forward and backward. Like a monk in his cell, there was nothing to distract me from the task I felt called to complete.

The hard part was starting, but once I did, the words gushed out of me like I’d slashed a swollen artery. I wrote for eight hours a day almost from the start, often taking meals at my little desk. I had the general shape of the book in my head, but at first I let my characters, who seemed so real to me, lead me where they wanted to go. My writing days edged up to ten hours, and my speed increased. A week passed like time in a dream, two weeks, three. Weekends were a quaint societal construct, no longer relevant to my existence.

As I approached the story’s midpoint, index cards in a riot of colors blossomed on my wall. It was time to start nudging my volatile characters into each other’s paths, to erect the obstacles that would force them toward conflict and climax. My sessions continued to lengthen. On my peak day I worked steadily for fourteen hours, spraying out 10,000 words in one long burst. I could scarcely tear myself away from the page.

In March, with disbelief, I typed the end. I stood up blinking from my chair, exhausted and empty. I couldn’t think what to do next. I had wakened from my vivid dream into a bleak, disappointing reality. But I could still point to what I’d created—a complete novel, something I hadn’t been certain was in me—and feel pride. The Revivalist weighed in at 707 manuscript pages, nearly 170,000 words. I’d written it in eight weeks.

In all the time since, I’ve never come close to producing so much fiction so quickly.

A first novel is an interesting beast. When I look back now at mine, I can see so many of the forces that were at work, forces I could never have identified at the time. The novel is set in a small religious town cut off from the rest of the world by a technological plague. The protagonist, a rational scientist, is only there because he was attending his father’s funeral when the disaster struck. He’s trapped in a town where he doesn’t fit in and where no one likes him, and it’s all because of his father.

It’s not hard to pick out the metaphor beating at the heart of this deservedly unpublished novel. In fact, if it weren’t clear enough already, the text underlines it time and again by giving nearly every major character a difficult or abusive father. Furthermore, the novel examines the role of religion in mob behavior and scientific illiteracy, portrays its prophets as either evil or deluded, and delivers its sex with an unhealthy infusion of terror.

A first novel tends to be a dumping ground for the issues its author has been dragging around since childhood. It tends to draw heavily on its author’s own experiences. It tends to transmute real-life weaknesses and failures into fictional strengths and triumphs. It tends to be more about its author’s world than its own.

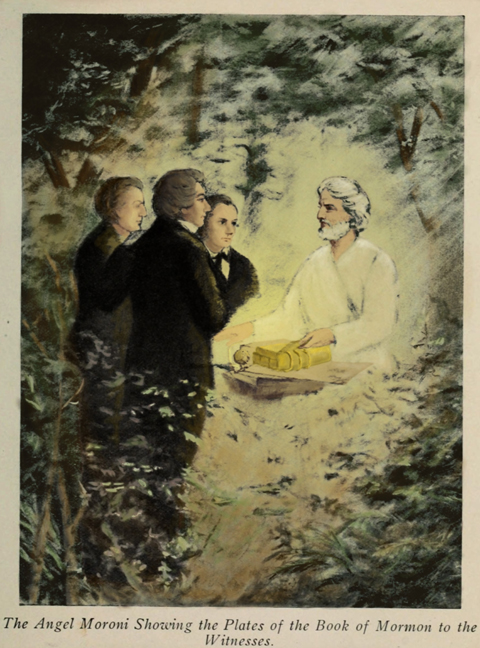

The Book of Mormon is a classic first novel. When Joseph Smith sat down to write, or rather dictate, his most well-known work, he was a fourth child creating a protagonist, Nephi, who is also a fourth child. He was a young man whose family moved relentlessly from town to town, sending his protagonist’s family on a decade-long pilgrimage through the wilderness. He was the son of a man who had dreamed a complicated dream about a fruit tree, recounting his protagonist’s father’s complicated dream about a fruit tree. He was a frontier magician putting glow-in-the-dark stones into the hands of his characters—not to mention giving them an enchanted compass that receives text messages from God.

Much of the language of the Book of Mormon, moreover, reflects the hot-button issues of Joseph’s day. The book’s prophets rail against “that great and abominable church, which is the mother of abominations,” which is how Joseph’s anti-immigrant contemporaries would have talked about the Catholic faith of the Irish arriving to work on the Erie Canal. The book denounces “secret oaths and combinations” as forcefully as New York’s most virulent opponents of Freemasonry. Its characters hold forth on topics ranging from infant baptism to the nature of the Trinity, about which Joseph would have witnessed much acrimonious debate.In short, the Book of Mormon is as much a product of its time and place as Joseph himself.

If Joseph’s authorship of the Book of Mormon seems self-evident to me now, when I was younger I found the question of its origin far murkier. This was something I struggled with throughout my adolescence and my time as a missionary.

As a connoisseur of swordplay and derring-do, I found parts of the Book of Mormon exciting as hell. But long stretches of it were so boring, especially the stuff lifted from Isaiah, that it wasn’t hard to see why Mark Twain would label it “chloroform in print.” More damning, though, were the inconsistencies and anachronisms that jumped out each time I read the Book of Mormon. Over and over I twisted myself into pretzels of logic to reconcile apparent contradictions. Over and over I prayed for the faith to make them make sense.

Take King Lamoni’s horses and chariots, for instance, from the 20th chapter of Alma. If we start from the assumption that the Book of Mormon is a genuine ancient artifact, more correct in its translation than even the Bible, then we must assume that the horse and the wheel were known somewhere in the Western Hemisphere at around 100 bce. These become two of the many pillars propping up the text’s authenticity. If archaeologists have failed to turn up any supporting evidence, then it only means that evidence is still waiting to be found, buried underground or perhaps swathed in jungle vines. Otherwise the structure of the Book of Mormon begins to creak and groan . . .

Of course, maybe Joseph did not literally mean horses. Maybe the original text referred to some New World beast unknown to him, and he chose the word “horse” as the closest equivalent in translation. But if that was true—another pillar cracking, plaster raining down—then why were animals called “cureloms” and “cumoms” mentioned later in the Book of Mormon? Why use made-up names for those and not for the thing that’s not really a horse?

And what about the steel, the wheat, the elephants, and more? Through sheer dint of will, I would shore up my shaky edifice by telling myself that better minds than mine, whole departments at Brigham Young University, were working on these problems, and that belief in any sacred text required a generous application of faith.

For my entire life, no one else around me seemed to have any trouble summoning up this faith. What was wrong with me that I found it so hard?

It would have been so much easier for me if I could simply have admitted to myself that Joseph Smith made the Book of Mormon up. But then again, that would have made so many other things so much harder for me that I couldn’t let myself entertain the thought.

If Joseph was no prophet, then my life was built on a foundation of sand.

Every Mormon child learns at a young age to love and revere Joseph Smith. To us, he is both a larger-than-life figure, renowned for his physical prowess and irrepressibility, and a paragon of humility, faith, integrity, and sacrifice. We believe, as later Mormon scripture declared, that he “has done more, save Jesus only, for the salvation of men in this world, than any other man that ever lived in it.” We feel so close to him that we know him by his first name, like we know our friends.

Joseph’s life gave us so many examples of how to live our lives with goodness, strength, and bravery. Take for example the story of his leg surgery, which was one we heard often in Sunday school. The self-possession and grit he showed as a child was just incredible, and so inspiring.

Joseph was at most seven when his brother Hyrum brought typhoid fever home from boarding school. The disease raged through the family, sparing no one. Both parents and all seven children survived, though for Joseph’s older sister, Sophronia, it was a close thing. Joseph himself developed a painful abscess, what he referred to as a “fever sore,” in one shoulder.

A local doctor lanced the abscess, which temporarily relieved Joseph’s discomfort but also let the bacteria into his bloodstream. The infection soon lodged in his left leg, where his tibia became inflamed with typhoid osteomyelitis. For weeks Joseph suffered unrelenting agony. His only respites came when the doctor returned, twice, to drain the resulting abscess, laying open the flesh all the way to the bone.

But the bone itself was infected and dying. A council of surgeons examined Joseph at home and agreed that he would die unless the leg was amputated. Joseph’s mother, Lucy, demanded they make one more attempt to root out the infection. It happened that the chief consultant, Nathan Smith (no relation), had pioneered a grueling technique for removing necrotic bone. He must have been reluctant to try the procedure on a child so young, but Lucy was adamant and the surgeons at last assented. Dr. Smith’s fee was a precious eleven dollars.

When the surgeons explained the operation they were about to attempt, Joseph’s overwrought father burst out sobbing at the side of the bed. Joseph himself remained relatively calm, agreeing to the procedure but refusing to allow the surgeons to tie him to the mattress. By Lucy’s account, Joseph told them, “I can bear the process better unconfined.”

The surgeons then insisted that he drink some brandy or wine to dull the pain, but Joseph refused that too. “I will not,” he said, “touch one particle of liquor; neither will I be tied down: but I will tell you what I will do, I will have my Father sit on the bed close by me; and then I will do whatever is necessary to be done, in order to have the bone taken out.”

Knowing his suffering would be too much for her to witness, Joseph sent his mother not just out of the room but out of the house entirely. The surgeons opened his leg with a crude scalpel that was probably a full foot long. They bored holes above and below the infected area of the tibia, then used forceps to break off pieces of the dead bone. Twice Joseph’s screams drew his frantic mother back into the room. The first time Joseph cried out that he could “tough it” if only she would leave. The second time, confronted by Joseph’s pale, sweaty face and the buckets of blood drenching the sheets and the surgeons too, Lucy had to be, in her own words, “forced from the room and detained.”

In all, the surgeons broke fourteen chunks of bone from Joseph’s tibia. He not only survived the harrowing operation but made an extraordinary recovery, though he walked with a slight limp for the rest of his life.

What Mormon child could hear this story and doubt for a moment that young Joseph was destined to become the greatest of all God’s prophets? What child could fail to be uplifted by his courage and purity, and his protectiveness toward his mother?

What, in other words, was not to love?

If this story strikes you as more horrifying than inspiring, you’re not alone. In his book Inside the Mind of Joseph Smith: Psychobiography and the Book of Mormon, psychiatrist Robert D. Anderson puts the incident under an analytical microscope, though the part he finds most horrifying may not be what you’d expect:

Mormon writers have used this story to suggest how good this future prophet was even as a child, and how much his parents cared. In therapeutic terms, this incident is not a commendable one. Joseph was a young child, possibly five, no more than seven, desperately protecting the emotional state of his parents even while he was undergoing a life-threatening crisis and extreme physical pain. The implication is that they were unstable and that, even at this early age, he has learned that his security depends on providing security for them.

Anderson calls this family dysfunction a “reversal of generations.” Viewed in this light, Joseph’s story becomes far more heartbreaking than heroic. In fact, the surgeon’s bloody scalpel, in Anderson’s reading, becomes the controlling image in Joseph’s emotional development. It appears time and again in the Book of Mormon in the guise of a great sword. We first see it when Nephi stumbles across a distant relative, drunk and passed out, who has tried to kill him and steal his family’s treasure. Nephi needs the scriptural records in this man’s possession, so the Lord commands him to take the man’s sword and cut off his head. A distant relative such as young Joseph may have taken Nathan Smith to be.

Thus is Joseph’s great childhood trauma transformed into triumph, turning the tables on his cruel tormentor.

Mormon apologists love to ask how an uneducated farmboy could possibly have written the Book of Mormon himself, especially given that the bulk of its 275,000 words were dictated in a span of two and half months. It must be genuine, they argue. How else can you explain it?

This thinking diminishes Joseph’s achievement, his genius at synthesizing Biblical language and thought with American preoccupations and ethics, his gift for improvisation on a theme. The more appropriate question would be how the Book of Mormon could have been written by anyone but this uneducated farmboy, this charming con man, this intuitive theologian—this Joseph Smith.